“D.C. and Puerto Rico should be states. Pass it on.” With passage of the D.C. statehood bill in the House of Representatives last Friday, variations on this statement have been gaining traction as a liberal rallying cry. Because they are not states, neither D.C. nor Puerto Rico have voting representation in Congress. The votes of …

“D.C. and Puerto Rico should be states. Pass it on.” With passage of the D.C. statehood bill in the House of Representatives last Friday, variations on this statement have been gaining traction as a liberal rallying cry. Because they are not states, neither D.C. nor Puerto Rico have voting representation in Congress. The votes of …

Continue reading "D.C. and Puerto Rico are not the same."

The post D.C. and Puerto Rico are not the same. appeared first on Legal Planet.

#puertorico #notthesame https://legal-planet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/1_21OctGNnV9KGewjPhcRjNA-400x300.jpeg https://legal-planet.org/2020/06/29/dc-and-puerto-rico-are-not-the-same/

“D.C. and Puerto Rico should be states. Pass it on.”

With passage of the D.C. statehood bill in the House of Representatives last Friday, variations on this statement have been gaining traction as a liberal rallying cry. Because they are not states, neither D.C. nor Puerto Rico have voting representation in Congress. The votes of Puerto Rico’s 3.2 million citizens also do not count in U.S. presidential elections (thanks to a constitutional amendment, D.C. citizens have been able to vote for President since 1961). If Democrat-leaning D.C. and Puerto Rico were to become the 51st and 52nd states in the Union, that’d be a considerable boon for Democrats looking to reclaim control of the Senate and the Electoral College. Statehood proponents also make the point that all Americans “deserve” equal representation.

No matter how attractive these arguments might appear on the surface, the idea that Puerto Rico “deserves” to be a state, just the same as D.C., overlooks a critical difference between the two.

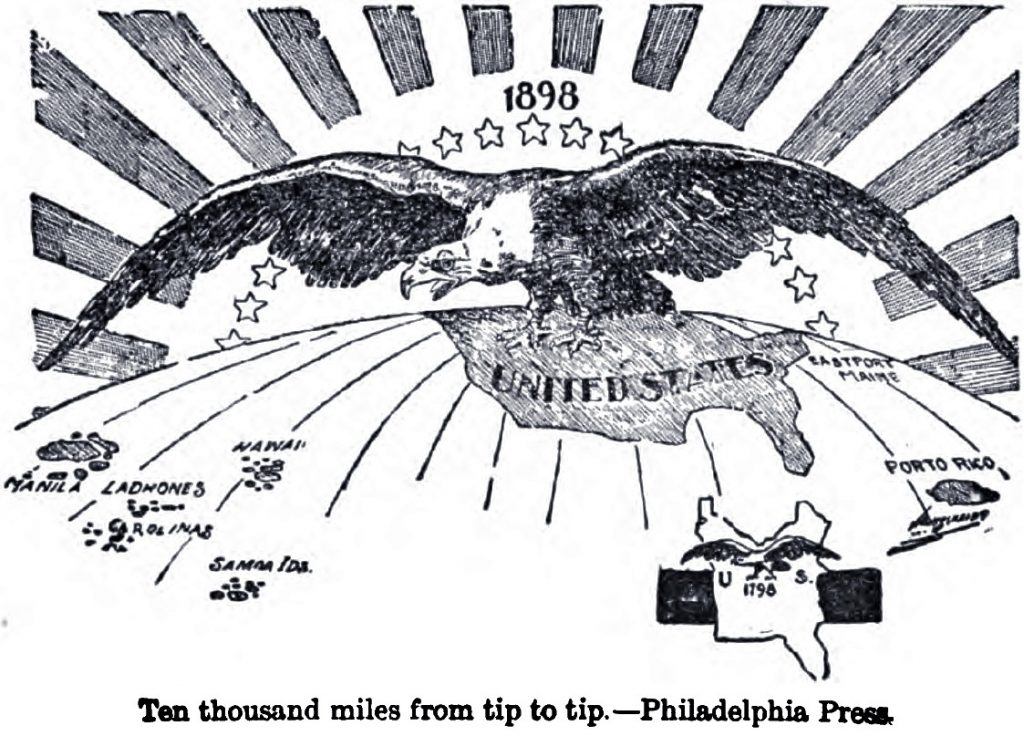

D.C. was established by the U.S. Constitution to serve as the nation’s capital in 1790. Puerto Rico was annexed by the United States in 1898 and has been subject to colonial rule ever since. While statehood may be appropriate for D.C., the same is not necessarily true for Puerto Rico.

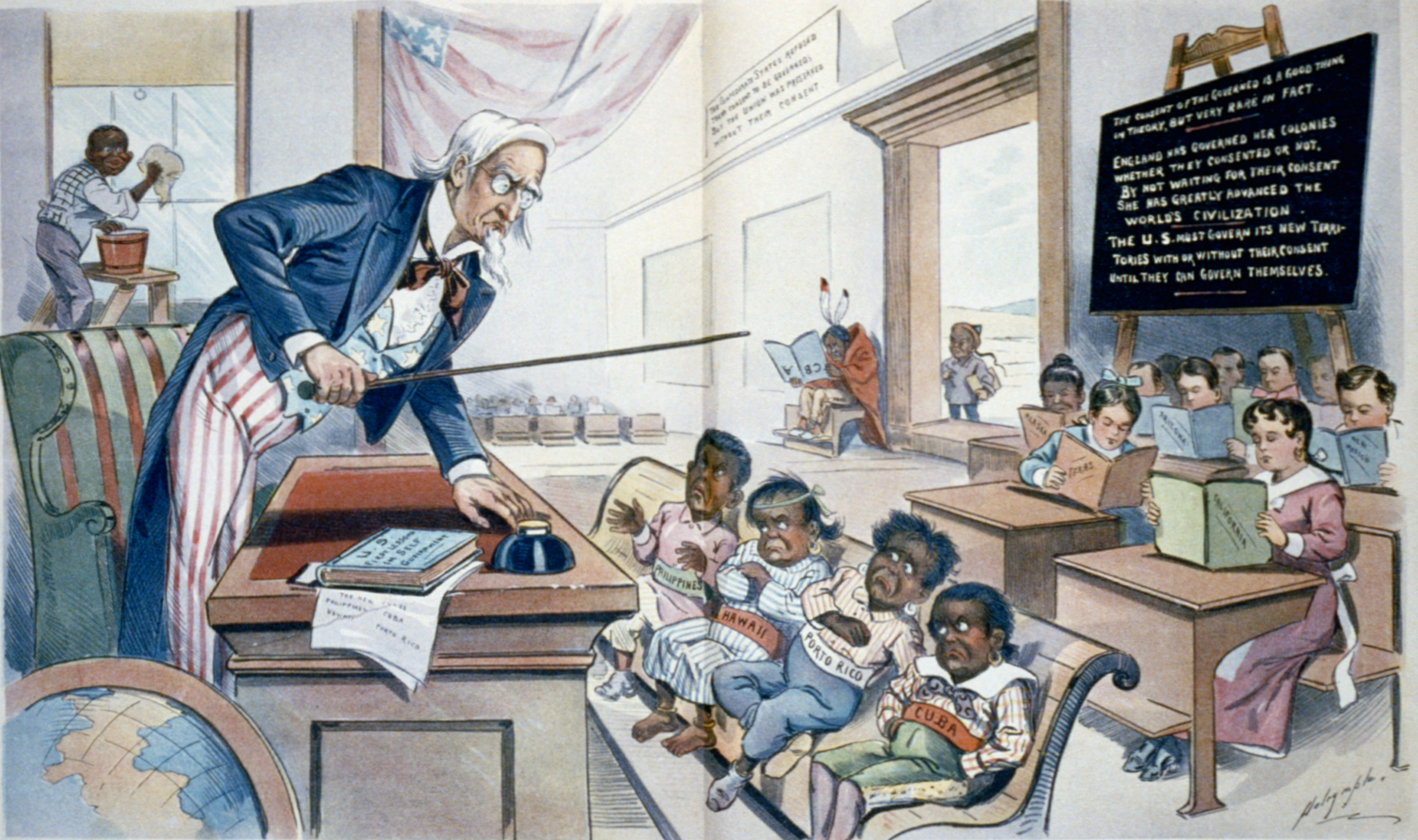

The United States claimed Puerto Rico along with Guam, Cuba, and the Philippines as spoils of the Spanish American War. At that time, annexed territories on the continent were automatically placed on a “path to statehood.” The Constitution applied in full in these territories and their inhabitants were extended U.S citizenship and voting rights. Then, once territories were sufficiently “American” in character—meaning enough Native people had been exterminated or dispossessed and enough white people had settled there—the territories would be granted full statehood. Hawai’i, which was annexed the same year as Puerto Rico, but which already was home to a substantial class of white capitalists, was placed on the path to statehood the same as territories on the continent.

By contrast, from the moment the U.S. annexed Guam, the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, statehood was out of the question. Racist conceptions of island peoples as inferior, savage, and strange foreclosed the possibility of statehood in the absence of white settler colonies. But white Americans did not want to move to these “primitive” islands. With statehood off the table, the question facing the United States became how to effectively maintain dominance over its strategically important new possessions without fully bringing them into the Union.

Ultimately, America’s “imperial problem” was solved by the Supreme Court in a series of blatantly racist decisions known as the Insular Cases.

In 1901, in the leading Insular Case of Downes v. Bidwell, the Court considered the question of whether the Constitution’s requirement that all taxes and duties be uniform “throughout the United States” applies in Puerto Rico. The Court decisively answered that no, the taxation provision—and the Constitution more generally—does not apply in Puerto Rico. In the Court’s view, applying the Constitution in Puerto Rico would lead to an absurd result: It would mean that territorial inhabitants, whether “savage or civilized” would be “entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities of citizens.” This could not be. Clearly, the “alien races” of the territories did not deserve the benefits of “Anglo-Saxon principles of government.”

Based on this racist logic, the Court went on to set out what has come to be known as the doctrine of territorial incorporation. In short, the doctrine provides that it is up to Congress to decide whether and to what extent the Constitution applies in territories. If Congress chooses to “incorporate” a territory, like Hawai’i, the Constitution automatically applies in full. But in unincorporated territories, like Puerto Rico and Guam, people do not enjoy Constitutional protections unless and until Congress chooses to extend them.

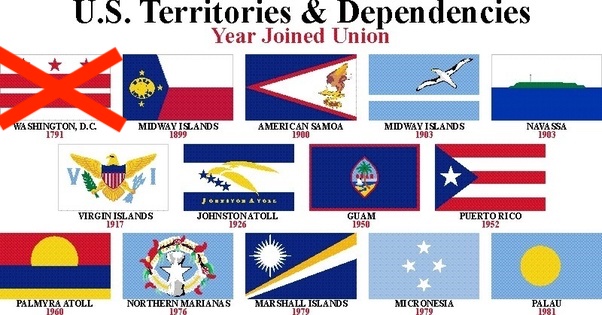

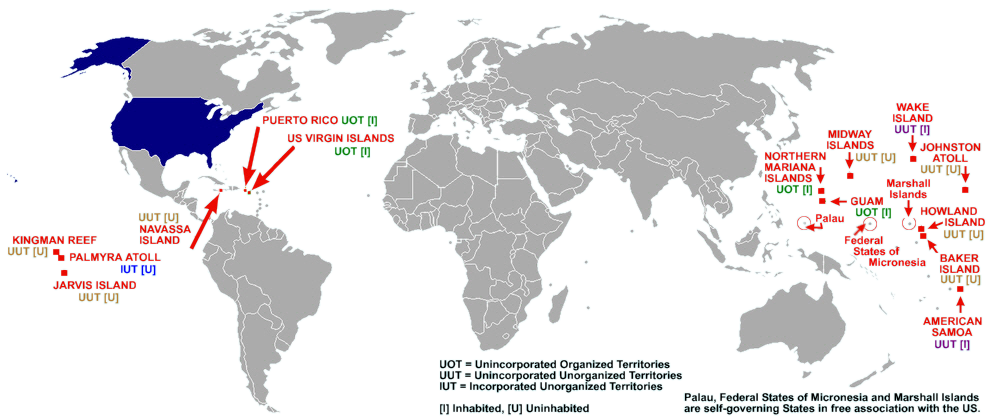

Twenty years later, the Court qualified that territorial inhabitants are entitled to certain “fundamental rights,” but what exactly this means remains uncertain. What is clear is that these “fundamental rights” are something less than those enshrined in the Bill of Rights. For example, territorial inhabitants likely do not enjoy 14th Amendment birthright citizenship. Puerto Ricans and Guamanians are citizens because Congress has given them this status legislatively. But the people of American Samoa, another U.S. territory, are not citizens because Congress has never extended them this status (and many American Samoans feel they are better for it). And, of course, territorial inhabitants do not have the right to voting representation in Congress or the right to vote for their commander in chief.

Grounded in racist notions, all of these restrictions are a product of the territories’ colonial status. In the words of the Supreme Court, unincorporated territories are “appurtenant,” “belonging to but not a part of” the United States.

To this day, the racist doctrine announced in Downes v. Bidwell and its progeny has been upheld and defended by the Supreme Court and every presidential administration (yes, even Obama) as an appropriate framework for administering the territories. It was on the basis of this racist doctrine that, in 2016, the Supreme Court held that territories, unlike states (and even Indian tribes) have no independent sovereignty. Rather, they are legally considered to be under the total dominion of the federal government.

The Court in Downes intimated that territories cannot be allowed to remain in this colonial limbo indefinitely. It would be a “violation of duty under the Constitution,” the Court explained, for the United States to “permanently hold territory which is not intended to be incorporated.” And yet, over 100 years later, this is precisely what the U.S. appears to be doing.

Though the Philippines and Cuba gained independence, Puerto Rico and Guam, along with the other inhabited territories—American Samoa (annexed 1901), the Virgin Islands (annexed 1921), and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (administered by the U.S. as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands from 1946 until it became an unincorporated territory in 1978)—continue to exist in their liminal, unincorporated space: Unable to exercise sovereignty yet unrepresented in the government of their colonizer. Exploited to assert American military and economic hegemony, yet largely outside the consciousness of the general American public. “Foreign in a domestic sense.”

I’ll say it again. Puerto Rico is not like D.C. Puerto Rico is a colony.

The remedy to colonization is not statehood, but self-determination—the right to be free from alien domination. Recognized as a jus cogens norm of international law, self-determination is a prerequisite to the full enjoyment of all other human rights. Self-determination means allowing the people of Puerto Rico, and of each of the other territories, to decolonize as they see fit—whether by seeking statehood, independence, or some other status.

In no case should statehood be treated as the only just or appropriate outcome for the territories. Look at the fate of Hawai’i. Statehood was foisted on the Kingdom of Hawai’i against the majority will and in service of a white, capitalist oligarchy. To this day, the incorporation of Hawai’i into the Union makes pursuit of native Hawai’ian decolonization nearly impossible.

Claims that Puerto Rico “deserves” statehood ignores the reality that it is a U.S. colony and that Puerto Ricans did not ask to be a “part” of this country (empire) in the first place. And using Puerto Rico as a political chip to be cashed in for more democratic votes—particularly without understanding the territory’s status—is more of the same colonial violence. Puerto Rico should not be made into a state in service of an American political party, or even in service of American democracy. If Puerto Rico becomes a state, it should be because Puerto Ricans say so.

In this moment, when the movement to dismantle systemic injustice seems to be at a zenith, perhaps we should try a new rallying cry:

“Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands should be liberated from colonial rule. Pass it on.”

The post D.C. and Puerto Rico are not the same. appeared first on Legal Planet.

By: Autumn Bordner

Title: D.C. and Puerto Rico are not the same.

Sourced From: legal-planet.org/2020/06/29/dc-and-puerto-rico-are-not-the-same/

Published Date: Mon, 29 Jun 2020 16:00:32 +0000

Vist Maida on Social Me

Website Links

Maida Law Firm - Auto Accident Attorneys of Houston, by fuseology

No comments:

Post a Comment